Rethinking Farming, Restoring the Earth.

Visiting the land and witnessing the diversity and abundance of insects like bees, hoverflies and dragonflies was truly beautiful. A key takeaway for me was when doing invertebrate habitat creation: You can’t simply plant one resource needed for a species lifecycle and expect it to survive. For example, your chance of retaining a population of ivy bees would not be very high if you simply plant ivy to encourage them. However if you created a sand pile for nesting habitat locally it would allow the ivy bees to survive, reproduce and maintain their population in the area. You must consider their full lifecycle: Where do they breed? Shelter? Forage? Nest? Drink?

As insects often have short lifecycles, with multiple generations in a single year, you must have all necessary resources available on your land, where possible of course.

Also, to encourage a diversity of insects (and consequent healthy diverse ecosystem), structural diversity is key. A variety in structure, on or above ground, helps to create a range of microclimates. This change in temperature, moisture and light conditions provide a range of habitat niches. Everything was evident in the deadwood structures present on John Little’s land where you could find a range of standing and lying deadwood pieces.

We learnt that by making deadwood habitats (with a variety of wood types, standing/lying positions and ages) create a change in microclimate; and substrate and levels of wood decay allow different saproxylic species (ones that rely on deadwood for part of their lifecycle) to survive.

Over the few past years I have been learning about regenerative agriculture after learning how harmful industrial agricultural practices are to the environment. If these destructive processes continue to deplete the soil and the ecosystems that fuel our food growing, we could lose so much topsoil and this will leave us unable to feed the world, converting land to desert, a story told many times before.

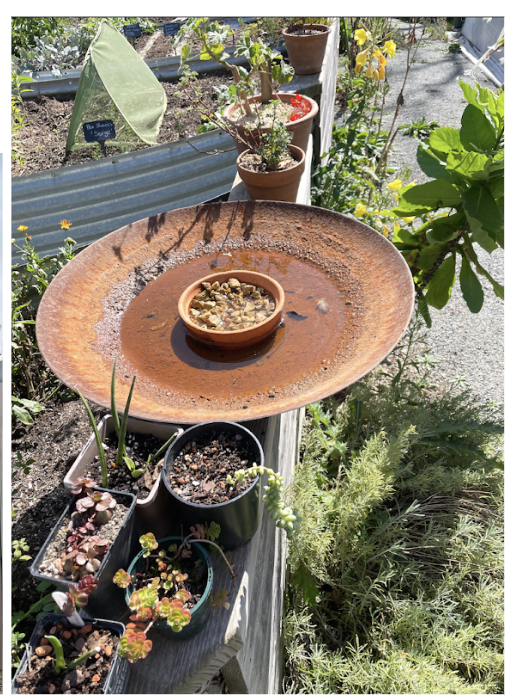

This year I have been exploring permaculture, which is a way of conscious design and holistic living to maintain agriculturally productive systems that still have the diversity, stability and resilience of natural ecosystems. These systems are ‘closed loop’ providing its own energy from ‘waste’, for example compost from food scraps and tree plant debris or water collected from roof runoff.

Rakesh from https://www.rootsnpermaculture.com/

Visiting a food forest was like stepping back in time and into the future. A food growing system inspired by people who lived in the tropics who engineered the forest by planting and spreading edible species that enriched the soil and wildlife. Food forests imitate the structures of many natural woodlands; large canopy trees, understory trees, shrubs, herbaceous layers, vines and belowground rooting networks.

At Martin Crawford's forest we got to eat edible leaves, roots, shoots and fruits i’d never seen at a market before but you could simply pick from all around you! We learnt about the medicinal properties of these plants and this form of growing made me feel like an active part of the ecosystem, so in touch and aware of the processes around me.

Witnessing the variety of food that can be grown in food forest systems was an awakening to how differently we could be using land. During the train journey we passed hundreds of acres of grazing and crop fields, barren, desertifying landscapes that do not sustain ourselves, wildlife, soil or climate.

If land was shared more equally with more people working directly with the land, applying permaculture principles, we could be growing so much more food while fighting the biodiversity, mental health and climate crisis as well as having a kinder and more harmonious society.

The Story Garden closed on Ossulston Street in September 2025 and we launched a massive giveaway and resource distribution project. It was a learning on